The story of Joseph Laroche is one that has, until relatively recently, been largely forgotten in Titanic memory and discourse. The lingering question concerns why this is the case. You would think that seeing a black man walking the decks of the ship with a white woman and their offspring would make a lasting impression on Titanic’s passengers, particularly the first- and second-class passengers, but little mention is made of Laroche or his family. It was only in the year 2000 that his story rose to prominence as a result of a Titanic exhibit in Chicago. This oversight helps explain the prevalence of the mythical Shine in African-American memory instead of Laroche.

Laroche was born in Cap Haiten, Haiti, on May 26, 1889 to a prominent Haitian family. His uncle, Dessalines M. Cincinnatus Leconte, was the president of Haiti from July 1911 until August 1912 when he died in an explosion. Laroche left Haiti at the age of fifteen to study engineering in Beauvais, France. While he was there, he met Juliette Lafargue, who lived in Villejuif, a nearby town. The two married in March 1908.

After he earned his engineering degree, Laroche was unable to find suitable employment in France because of his skin color. Laroche had a wife and two young daughters that he wanted to support on his own, without the help of his father-in-law. Shortly after he learned that Juliette was expecting a third child, Laroche decided that he should return to Haiti with his family while his wife was still able to travel. Initially, the family was to travel on the French liner La France, however the liner’s strict policy required children to remain in the ship’s nursery during meal times, which didn’t appeal to the Laroches. They exchanged their first-class tickets for second-class tickets on the Titanic. The family boarded the ship at Cherbourg, France on the evening of Wednesday, April 10.

In her article about the Laroches, “What Happened to the Only Black Family On the Titanic?” Zondra Hughes asserted that race was an issue aboard the ship and that the Laroches’ presence elicited insults and crude behavior directed at them by crewmembers and fellow passengers. Hughes was not alone in her assertions. A press release that appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer about an exhibit featuring the Laroches stated that racism was rampant on the ship and the family had to endure derogatory comments and behavior. However, a letter that Juliette wrote to her father while the Titanic was at Queenstown, Ireland, paints a different picture. She did not mention any racially motivated incidents directed at her or her family. In fact, she wrote that they had become acquainted with another French family, whom they had traveled from Paris with on the train and dined with onboard the ship. She also wrote that “the people onboard are very nice.” It should be kept in mind, however, that when Juliette Laroche wrote her letter, she and her family had been aboard the ship for less than 24 hours. They would spend four more days at sea – plenty of time to experience the conditions outlined by Hughes and the Inquirer.

Little has been written about the Laroches in survivor accounts of the sinking, which is surprising. Nowhere in the 1912 press descriptions of the ship and the interviews with the survivors was the presence of a black family among the passengers ever mentioned; in fact, this information has come to light only relatively recently through the efforts of French researcher Olivier Mendez. It seems really strange once you take into account how eager surviving passengers and crew were to disparage other ethnic groups. It became such a problem that the White Star Line was forced to apologize for derogatory statements made by Titanic’s crew about ‘Italians’ (a generic term for all the darker-skinned passengers) and their behavior during the last moments on the dying ship.

The only mention of Simonne and Louise Laroche, Joseph and Juliette’s daughters, was made by Kate Buss in a letter home: “There are two of the finest little Jap[anese] baby girls, about three or four years old, who look like dolls running about,” she wrote. On Sunday night, as passengers became aware of the ship’s peril, Joseph, who spoke fluent English, learned of the ship’s condition and quickly placed his family in a lifeboat. Laroche is believed to have perished, and his body was never recovered. Juliette and her children completed the trip to New York aboard the Carpathia. Once there, Juliette decided to return to France with her daughters on a French liner, and she moved back into her father’s house in Villejuif. She gave birth to her and Joseph’s third child, a son, in December 1912. After suing the White Star Line for damages, Juliette was awarded 150,000 francs in 1918. She used the money to open a fabric-dying business to support her family, which had lived in poverty throughout the First World War. Neither Juliette nor her daughters devoted much effort to speaking publicly about the event. Juliette only discussed it with a handful of close friends, and her daughters followed suit for the better part of a century.

According to the Titanic Historical Society, Louise Laroche was a member of the organization from its beginning in 1963 until her death in 1998. Despite Laroche’s membership, however, communication between her and the organization was thin due to language barrier (she only spoke French). The silence was finally broken when Oliver Mendez, who is fluent in French and is also a THS member, visited Laroche at her home in France. The story of that meeting, and ultimately of the Laroches’ passage aboard the Titanic, appeared in the Titanic Commutator, THS’s periodical, in 1995.

Since Mendez’s meeting with Louise Laroche, the Laroches’ story has gained more notoriety. Judith Geller’s book Women and Children First, as well as a traveling Titanic exhibit featuring the Laroches, took giant steps toward publicizing their story. The exhibit’s first location was the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry in 2000. The exhibit ran for seven months in Chicago and visited a number of other cities, including Seattle, Los Angeles, Paris, and London. This was the first exhibit to tell the story of the Laroches. Within the exhibit, two program interpreters portray Joseph and Juliette Laroche. The exhibit takes a necessary and admirable step in portraying the couple, however, issues concerning the memory of the couple arise with the portrayal. The actors portraying the Laroches are both black; in reality, Juliette Laroche was Caucasian. This calls into question the accuracy of the memory of the Laroches that is being perpetuated, but those involved with the exhibit have brushed aside any qualms about Juliette’s portrayal by a black actor. One of the actors who has portrayed Juliet has said that she doesn’t believe her portrayal of Juliette is historically inaccurate. “I’ve seen her picture, I’ve seen her features,” she said. “She definitely looks like she could have been mixed to me.”

The sinking of the Titanic was a tragedy, without a doubt. Fifteen hundred people died when it was within the technological means of the day to save them. Titanic was traditionally been judged to be historically insignificant, important only to enthusiasts and buffs. Utilizing traditional barometers of historical value such as economics and politics, the conclusion that the Titanic disaster is insignificant is valid. However, if the event is viewed from a different perspective, one that takes into account the cultural ramifications of the ship and the sinking, Titanic appears to be far from insignificant, and many new avenues of study and research present themselves.

One of those areas is the connection between African Americans to the Titanic. Outside of Leadbelly’s famous blues song about the ship and the legend concerning Jack Johnson’s attempt to book passage, there really has been no discussion of the Titanic in relation to blacks. Look a little deeper, however, and one discovers that the Titanic and blacks were not so distant from each other after all. While the mainstream press missed the connection, one nevertheless existed. Blacks, despite their apparent distance from the disaster, were more than merely aware of it. They infused it with their own collective memory of it through oral traditions, such as blues songs and most notably through the Titanic toast and Shine.

The connection transcends even this pseudo-link. A black man and his family traveled in second class on the Titanic. While Joseph Laroche was Haitian and not technically African American, the presence of a man of African descent aboard the Titanic was extraordinary. The fact that he traveled in second-class accommodations, rather than third-class, also adds to this fascinating tale. Even more remarkable is that this story has been obscured from the popular history of the Titanic until relatively recently.

Joseph Laroche’s story and the history Titanic toast phenomenon have not been obscured by any deliberate means, but as a result of cultural circumstances and differences. Despite these circumstantial hurdles, stories like Laroche’s and Shine’s are reasons that people persist in studying the Titanic and history at large. They also provide reasons for why historians should not hastily dismiss seemingly insignificant events as lacking historical value. So many stories have yet to be told, and sometimes those stories are found in the most unlikely places with the most unlikely people.

Sources:

Barczewski, Stephanie, Titanic: A Night Remembered, London: Hambledon and London, 2004.

Beesley, Lawrence, The Loss of the S.S. Titanic: Its Story and Its Lessons, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1912.

Biel, Stephen, Down with the Old Canoe: A Cultural History of the Titanic Disaster, United States: W.W. Norton and Co, Inc., 1996.

Confino, Alon, “Collective Memory and Cultural History: Problems of Method,” in The American Historical Review, Vol. 102, No. 5,Dec., 1997, pp. 1386-1403.

Everett, Marshall, Wreck and Sinking of the Titanic: The Ocean’s Greatest Disaster, Edison, New Jersey: Castle Books, 1998, 1912.

Fabre, Genevieve and Robert O’Meally, History and Memory in African American Culture, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Geller, Judith, Women and Children First, New York : Norton, 1998.

Gracie, Archibald, The Truth About the Titanic, Mitchell Kennerly: New York, 1913.

Howells, Richard, Myth of the Titanic, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999.

Jackson, Bruce, Get Your Ass in the Water and Swim Like Me: Narrative Poetry from Black Oral Tradition, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1974.

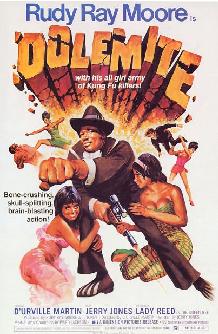

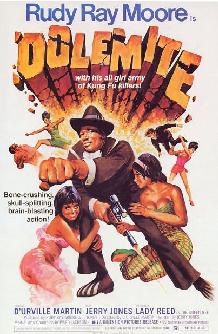

Jones, Jerry, Dolemite, Santa Monica, CA: Xenon Pictures, 2002, 1975.

Lord, Walter, A Night To Remember, New York : Bantam Books, 1997, 1955.

Moore, Rudy Ray, Eat Out More Often, Los Angeles: Kent, 1971.

Rasor, Eugene, The Titanic: Historiography and Annotated Bibliography, Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press: 2001.

Lord, Walter. The Night Lives On. New York: Morrow, 1986.

Pellegrino, Charles. Ghosts of the Titanic. New York: William Morrow, 2000.

Tibballs, Geoff. The Titanic: The Extraordinary Story of the ‘Unsinkable’ Ship. Pleasantville, New York: Carlton Books Limited, 1997.

Davie, Michael, Titanic: Death and Life of a Legend, New York : Knopf : Distributed by Random House, 1987.

Butler, Daniel Allen, Unsinkable: The Full Story of the RMS Titanic, Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1998.

Hughes, Zondra, “What Happened to the Only Black Family on the Titanic?”, Ebony, June 2000.

Hull, Diane. “The Toast of the Titanic Oral Tradition Carries On Legend of Lone African American,” in Washington Post, December 20, 1997; Page F01

Miller, Sabrina L., “Untold Story Of The Titanic,” in the Chicago Tribune February 20, 2000.

“Astor Put Boy By Wife’s Side.” Worcester Evening Gazette. 19 April 1912.

“Astor Saved Us, Say Women.” New York Times. 22 April 1912.

“Benjamin Guggenheim.” New York Times. 16 April 1912.

“Brooklynites Are Lost as Titanic Sinks.” Brooklyn Daily Times. 16 April 1912.

“Ismay Condemned for Taking a Boat.” Washington Times. 19 April 1912.

Mackay, Gordon. “Mrs. Candee Tells of Tragic Scenes as Steamer Sank.” Washington Times, 19 April 1912.

“San Francisco’s Assessor Tells Story of the Wreck of The Titanic.” San Francisco Bulletin. 19 April 1912.

“Says Ismay Took First Boat.” New York Times. 19 April 1912.

“Tells of Rescue from Titanic.” Galesburg Evening Mail. 23 April 1912.

“Titanic Survivor Writes of Horror to Friend Here.” Evening Bulletin. 20 April 1912.

“Two Survivors Call on Mayor to Ask Relief.” Evening World. 22 April 1912.

Encyclopedia Titanica, http://www.encyclopedia-titanica.org

“A Haitian Family Which Traveled in Second Class Aboard Titanic,” The Titanic Historical Society 10 November 2008, http://www.titanic1.org/people/louise-laroche.asp.

“Laroche’s – Haitian Family’s Dramatic Story On Board The Titanic,” Titanic – Nautical Society and Research Center, http://www.titanic-nautical.com/RMS-Titanic-LaRoche-FI.php.

“Passenger and Crew Information.” WebTitanic. http://www.webtitanic.net/framenumber.html.

Sultana Disaster Online, http://sultanadisaster.com

Titanic Historical Society, http://www.titanichistoricalsociety.org.